Cuddle Buddies: A Short Film Case Study Part 4 - Post-Production

The Fourth Part in a series of articles on how I made my short film Cuddle Buddies as writer, director and producer, from the writing phase all the way through post-production and beyond.

Previous Installment:

Cuddle Buddies: A Short Film Case Study Part 3 - Production

Previous Installment: The Short Film Here’s a link to the completed film, which serves as a great reference and context for all of the posts and discussions previously and to follow. Here is a link to the second article in this series. I highly recommend checking that out along with Part 1 since it serves a logical progression and context for this third pa…

The Short Film

Here’s a link to the completed film, which serves as a great reference and context for all of the posts and discussions previously and to follow.

Here is a link to the third article in this series. I highly recommend checking that out along with Part 1 & 2 since it serves a logical progression and context for this fourth part.

What is Cuddle Buddies?

Cuddle Buddies is a narrative dramatic short film that is independently produced and character driven. The logline is as follows: Cuddle Buddies tells the story of Lucy, a single mother who works as a professional cuddler in order to support her young daughter and to alleviate the loneliness not only in her clients, but also in herself.

I wrote, directed, edited, produced & colored this film and it very much was a labor of love in the truest sense of the word.

Why a Case Study?

The process of creating this film and seeing it through from the idea phase to the physical production and completion was an extremely difficult process and journey, and there were a slew of pitfalls I only wish I had known before embarking on the making of this film.

I fully realize that filmmaking is very much an art that requires you to learn and make mistakes as you do it, and the doing of it will always be the most essential ingredient and teacher. But if I can shed some light on some things I learned along the way, even if just to function as an educational tool and save any aspiring filmmakers working on upcoming projects, especially short films, the heartache of additional stress in the pre-production and production phases, then I have achieved my goal in documenting the entire production process through this case study.

OK so with that setup, let’s get into the fourth part of this series, which focuses on the post-production and completion of the short film.

Completing Production…

We had wrapped the three day shoot for Cuddle Buddies at the very end of June of 2019 and at that point, my primary goal was to take a break to rest and recover from the intensity of the entire couple months beforehand that encapsulated the bulk of pre-production and the shoot.

As is customary for me for virtually every project I create, I take around 2 weeks away from looking at any of the footage or working on the project to give myself distance and a mental objectivity and thus clarity on the project when I do dive back in with a refreshed mind.

There have certainly been exceptions when certain projects have a much tighter deadline to be completed for festival submission deadlines, former class projects or client deadlines, but I far prefer to take my time on my own films and build that longer runway into my post timelines to really experiment and tinker with every single option I can with the footage that was captured.

I also love to do anything that is not related to filmmaking, writing or even watching films while I take this break; mainly to avoid burnout following a rigorous shoot.

Logging the Footage

Logging the footage, (watching and organizing every single clip) can be both an invigorating and an agonizing process, and oft tedious and time-consuming. It’s thrilling when you notice subtle nuances in actor performances, camera movement and rhythms that you never could have detected on the shoot, since so many pieces are moving simultaneously. It’s also gut-wrenching when you feel that you did not record what you needed for the edit.

It’s a very common phenomenon to see a completely different performance in the editing room than you recall capturing on the set. This is why more takes is always preferable if you can afford it.

It can be a thrill when you’re pleasantly surprised by the subtle and nuanced work of an actor and it can be agonizing when you realize that a technical issue derailed the entire take. Whether the focus went soft, or the camera got bumped, a boom or crew member is in the shot, etc. It only takes one small detail to throw off a perfectly good take for every other element.

Sometimes it can just be a small detail, such as the timing of when a moving camera lands on a mark, in conjunction with an actor hitting their mark that just doesn’t feel right. Sometimes it’s unquantifiable, but as the filmmaker you just know what it should look like and what it shouldn’t, even if it’s off by just a hair. These are the details that a film can live and die by.

The good news is with clever editing and problem solving, there is usually always a solution around these kinds of issues. Something I’ve learned by now is not to panic, even if you don’t have a take where everything goes perfectly. With technological advancements in software and more affordable Visual FX (VFX) solutions, oftentimes there is also a digital CG fix that can create an elegant solve, when all feels lost; though additional costs will always be incurred for this type of solution. As long as you shot additional coverage or have budget to spare, there is a will and a way forward.

The Logging Process

At this time, I want to emphasize that I am not an editor by trade, but I have worked in post-production departments on larger features and I have been editing my own films I’ve directed for the last 12 years, so I will outline my process and what works for me, but want to stress that this is by no means the only way to do it or even perhaps the right way in a conventional workflow or pipeline.

One benefit, and perhaps a downside to some, is that as the writer and director, I can log the footage with the lens of the director and writer, assessing every nuance of the spirit of the film from the very beginning. I have always seen this as a positive and not a negative, with the caveat that showing rough cuts to objective viewers and colleagues along the way is absolutely essential before completion of the film.

I take my time to view every single clip from every single card (or mag) and really analyze what my favorite select takes are, first from every setup and then from every scene. Taking your time with this process helps avoid viewing fatigue, but also allows you to rewatch on subsequent days and really determine if your favorite takes are still your favorite takes over a number of days, and if they are, then you can really feel confident about putting those down to start from.

Organizing The First Cut

Editing is all about organization, so one of the first things I’ll do, even before logging footage is I will start a new project on a digital NLE (Non-linear editing system; IE: Premiere, DaVinci, Final Cut, etc.)

My preferred NLE is DaVinci Resolve for every step of the post process. Not only is it a free software but you can transcode, edit, color grade, and export all without ever leaving the same software. However, on this project we used Adobe Premiere to edit and did a roundtrip workflow from Premiere to finish color and final exports in DaVinci Resolve. Though it would have been far easier had I stayed in DaVinci all along.

Once I start a new project file on the NLE, I import the footage and then I create a “Master Timeline”, where essentially all of the footage and audio files will get thrown onto a big timeline.

First I’ll sync every take of audio to its corresponding video file, and hope that my sound designer labeled the files properly and neatly for ease of finding and syncing. Of course finding the “spike” for the slate clap in the audio file and pairing it with the moment in the video where the clapper touches the slate is the easiest way to sync, though you can use software like Plural Eyes to assist with this to expedite this process.

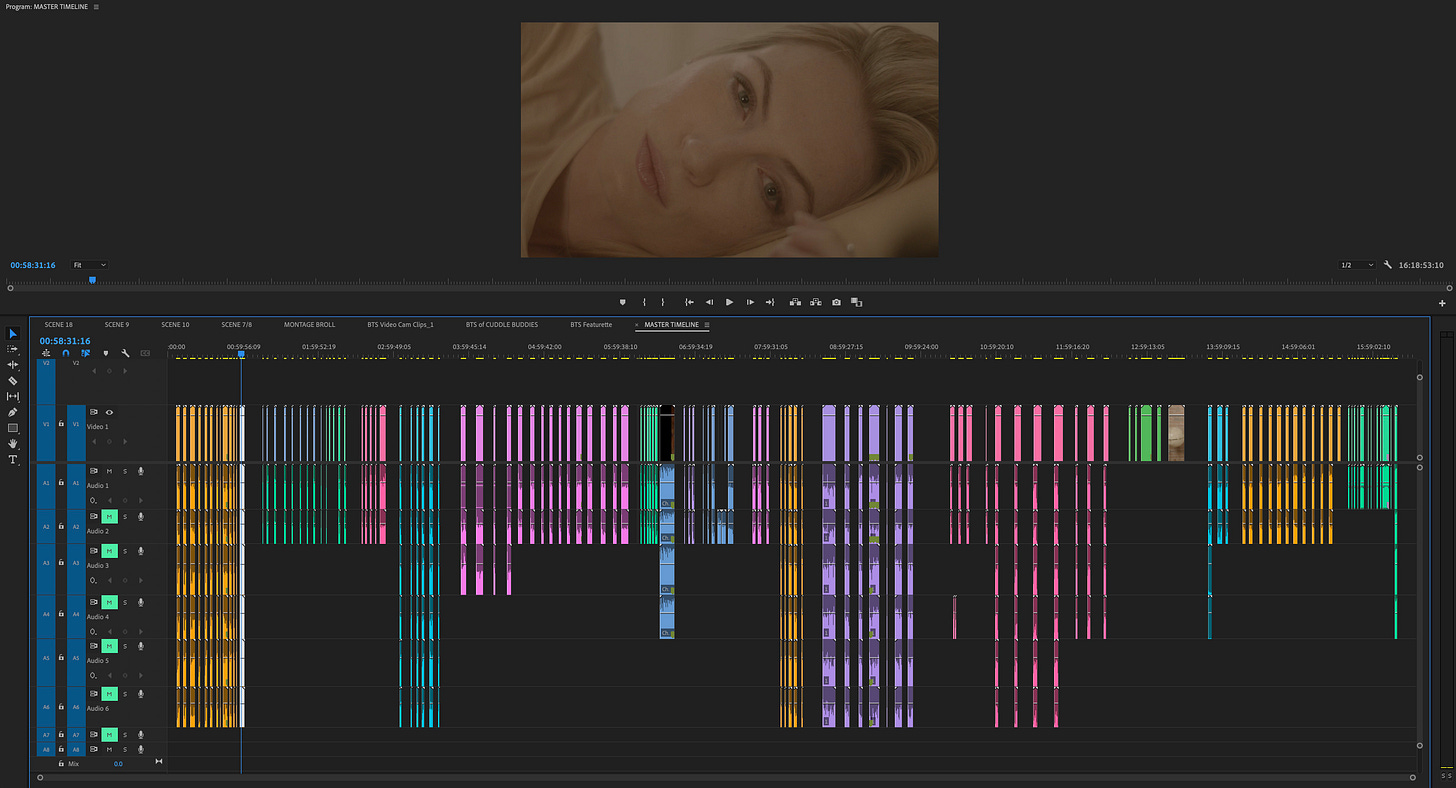

Once everything is synced up on the timeline, then I will go through and create a big gap between every “scene” as labeled in the script and then I will color code every clip within a specified scene to have it’s own unique color for ease of viewing on the timeline. For example: Green Colored clips for Scene 1, Red clips for Scene 2, etc. See an example below for reference:

It’s also helpful to label each clip with the scene Number and letter and take #, for example: Scene 1A, Take 1 would be labeled on that respective clip. Good organization simply makes editing much faster, since you can find any clip rapidly.

Once every clip from every scene is labeled on the master timeline, then I watch through every clip from every scene, though I prefer to tackle only one scene per sitting at a time to solely focus on that one scene. This tremendously helps avoid eye fatigue and a tendency to scrub through a clip for speed, which can lead to missing some great subtle moments within.

KEY TAKEAWAY 1: For me, I have found that a cornerstone for editing my own projects is to truly give it the time to move slowly and edit in chunks of time to keep myself sane and motivated, especially on an intricate edits with days of footage to sort. If you are working on a feature film or a television show, you will have a full post production team complete with assistant editors who help log, label and organize footage and media, and can move at triple (or more) the speed of a single editor, but when budgets are tight and it’s only you doing the editing, building in more time and rest is essential.

Editing Scene By Scene

Once your master timeline is synced up and labeled, the next step is I create a new timeline labeled specifically for each scene. The easiest way is to duplicate the master timeline and delete all of the clips that aren’t from that scene and do that for each scene.

When logging each scene, I pick out my top 1 to 3 takes of every camera angle (setup) and color code that with its own color to separate it from the rest. Even if there is just a section of that clip that I love, I’ll color the clip to insert it later. I use the color pink to label a clip if I have an absolute favorite take over the others.

I will always review every clip in every scene multiple times and then I come back and do it again the next day to see if any of my preferences changed and sometimes they do. Use time as a valuable asset to editing. Time will always narrow your vision and weed out the weaker choices.

Once I have picked all of my favorite takes from every setup, I then move all other clips to the back of that scene’s timeline and I arrange all of the 2nd or 3rd best takes closer to the front, and then I pick my favorite or one of my favorite takes from every angle and put them together toward the very front (or far left) of the timeline to start the first pass of that scene’s edit.

I’ll then go through and try to edit a cohesive version of that scene without getting too nit-picky yet about the more precise cuts or continuity. I’m mainly trying to get it down on the timeline to be somewhat visually seamless. Once I feel remotely satisfied with the first pass of the scene, then I often move onto the next scene.

For me, it’s much easier to tackle the edit only one scene at a time and then move to the next one. I don’t necessarily edit in chronological order going scene 1 to scene 2 to 3, etc. Sometimes I will tackle the much shorter and “simpler” scenes first. Sometimes it’s a good way to get the ball rolling and gain some momentum and choosing scenes with less dialogue/footage to choose from is a great way to dive in and build your motivation and rhythm early on.

The First Full Rough Cut

Upon completion of editing every scene together in rough form, the next stage is to create another timeline labeled “Rough Cut V1” or something of the like. In this new timeline I will copy the rough version of each scene from its respective timeline and paste the grouping of clips together in this new timeline. I will do that for every scene until they are all in this V1 timeline and then I mash all the clips together so they are next to each other.

At this point I take note of how long the runtime is and am very often shocked that it is usually way longer than you thought it could be, but this is very normal. Cutting down becomes the goal of subsequent revisions and will naturally occur as you often find a lot of seconds can be cut that drag the pacing along.

The very first cut of Cuddle Buddies was a whopping 30 minutes! The final cut is half of that, but it is always better to start with more to arrive at less.

After putting it all together for the first time, I like to sit back, hit play and watch the first cut without any distractions to soak in how the very first iteration of the film feels. Flaws and all, this is an exciting moment to see the shape of your movie for the first time.

The Second Cut and Beyond

After the first cut is complete is really when I start to analyze the film more meticulously, with an eye for details and looking at where I can cut out extra time and establish a clear cutting rhythm.

Feedback From Colleagues

As early as the first cut is fair game to seek out feedback from trusted colleagues. The key word here is trusted. I would highly recommend not sending it to people who are not in the industry and who aren’t fully aware of the post production process, at least not yet. I’ve often found the notes at this stage might not be as helpful or might be elements you’re already fully planning to implement.

Whereas sending it to other filmmakers I find more helpful, since they often have an understanding of how to watch it and can offer invaluable feedback that provides great ideas for the next cut and sources of brainstorming.

I think allowing your mind to stay open through the entire editing process is crucial, to allow for more great ideas to enter the door, even at late stages of post.

Generally, I’ll wait until closer to the 3rd or 4th or a later cut to send out to colleagues to look at, since it will be closer to the picture lock version, and ideally they won’t have to look at it more than once. My rule of thumb is never to assume anyone will look at your cut more than once. Sometimes they won’t even watch it one time, and that’s alright too. You can always go down your list.

Some of what becomes the focus of subsequent edits is the incorporation of the feedback from the colleague(s) you send it to, should you choose to implement any of the suggestions. So for example, in let’s say my 4th cut of the film, my sole focus of that cut is just to try to implement to the best of my ability, some of the notes from the feedback provided. Sometimes this is much easier to implement, and sometimes certain changes just aren’t possible with the footage you have and the assumption that no reshoots are possible.

Good feedback though will take into account your limitations and give you notes you can still readily implement with what you have.

Another note I want to stress is that as the creator of the film, you will ultimately know that film better than anyone else will, so it’s very important to take at least a few days after getting feedback to marinate on it and decide if it is really something you want to incorporate or not. While well intentioned, sometimes it is better not to take specific feedback if it alters your story, and execution from the film you set out to make in the first place.

I’ll give an example of some feedback I ultimately did not incorporate for the betterment of the film. A filmmaker that I tremendously respect and has a lot more experience than I do was gracious enough to take a look at one of the later cuts of Cuddle Buddies.

He called me up and had many thoughts about what the film should be, but from his vantage point. He told me I should cut out a whole half of the beginning and shift the focus of the conflict and stakes about the family drama with Lucy, her daughter and husband, and just focus on the clients and showcase more of “the intimate space normally reserved for lovers”. To be honest I thought I had to implement all of this and it really sent my head for a spin, since I nearly tried to do what he suggested and try a major swing and rethink my entire narrative approach in the edit.

After sitting on it for a week, I came to the epiphany that that version is not the movie I set out to make, and to be quite honest I didn’t want to see the movie of that version he preferred to see. I ultimately realized I didn’t know how to make that version, didn’t know what that even looked like and I would only have been doing it to make him happy. The best decision I realize looking back was to thank him for his time and quietly continue on the specific path I had already been walking for so long. In hindsight it was 100% the right call.

KEY TAKEAWAY #2: Know when to incorporate feedback and when to leave it. Oftentimes you can bring some ideas in and leave others out and strike a balance. Sometimes it serves you to incorporate all of it. But be sure to give yourself adequate time to make that call upon receiving the feedback.

Working With Another Editor

A little before we had shot the film, through Facebook I had met a fellow filmmaker and editor named Anderson Seal, and during our introductory phone call I had first talked to him about potentially producing the film, but when the timing didn’t work out, he had expressed interest in helping on the post side and doing some additional editing on the film.

Fast forward to post-production and I reconnected with Anderson and he was very excited to try his hand at a few passes of the film. Looking back, it was the greatest decision I made during the early post period.

At this point I had completed the first few initial rough cuts to give the film a basic structure and get a start on the editing. Anderson and I then decided that our workflow would be to do our own pass to further the cut along, and then pass the Premiere project file back and forth to each other to open the new timeline we had created and view what new edits had been made by the other.

We had to get together at the beginning to exchange hard drives to share all of the video, audio clips and all other assets and media so that whenever we opened the updated project file, it would automatically relink to all clips on the timeline in the appropriate place.

Major Editing Breakthroughs

This is where I will continuously sing Anderson’s praises and emphasize the importance of having another pair of eyes on the edit of any project. The ideas and synthesis of our two heads together created some incredibly creative and unconventional decisions that I certainly would not have ever come to on my own.

Early on, I really followed the script as far as the structure and chronology of scenes were organized and in those early cuts, it follows the script verbatim. The problem with this became that we had two separate cuddle scenes that both were extremely long and at times repetitive. This drove the runtime to closer to 20-25 minutes, which I knew was just way too long.

The other issue was that in those older cuts, we didn’t establish the narrative stakes as clearly as early in the film as we could have. The stakes were the fact that Lucy might potentially lose her daughter Marina to an insidious custody battle with the ex-husband James, who is positing that her work is sex work in court to make her look like a bad mother. The stakes are the reason we want to invest and care about Lucy and her central conflict and a general rule of thumb in any great film is to establish this as early as possible so you engage and hook your audience into caring about the protagonist and keep them interested, which is easier to do the earlier you grab them.

The genius in Anderson’s input were the following two breakthroughs:

Breakthrough #1:

We had a scene toward the very end of the film, where Lucy is on the phone with her divorce lawyer and it clearly outlines the fact that James is trying to take full custody of Marina away from Lucy and this sets her into a heartbroken rage and is a highly emotionally charged scene that Kaitlyn performed beautifully. In essence it really gives us sympathy for Lucy and makes us feel for her and want to root for her.

In the early cuts, this scene came as the penultimate scene in the film and in the script. Anderson suggested that we swap this scene to be the third scene we see in the film so that it introduces us to the stakes much earlier so that we care for Lucy earlier on and it carries throughout the duration of the film.

I swapped the scene on the timeline and it took five minutes and worked beautifully and didn’t break anything else in the edit. What an elegant solution that completely strengthened our structure in one fail swoop. This is another reason not to be completely bound to the script even in the edit phase, since breakthroughs can come at any moment and from any source.

Breakthrough #2:

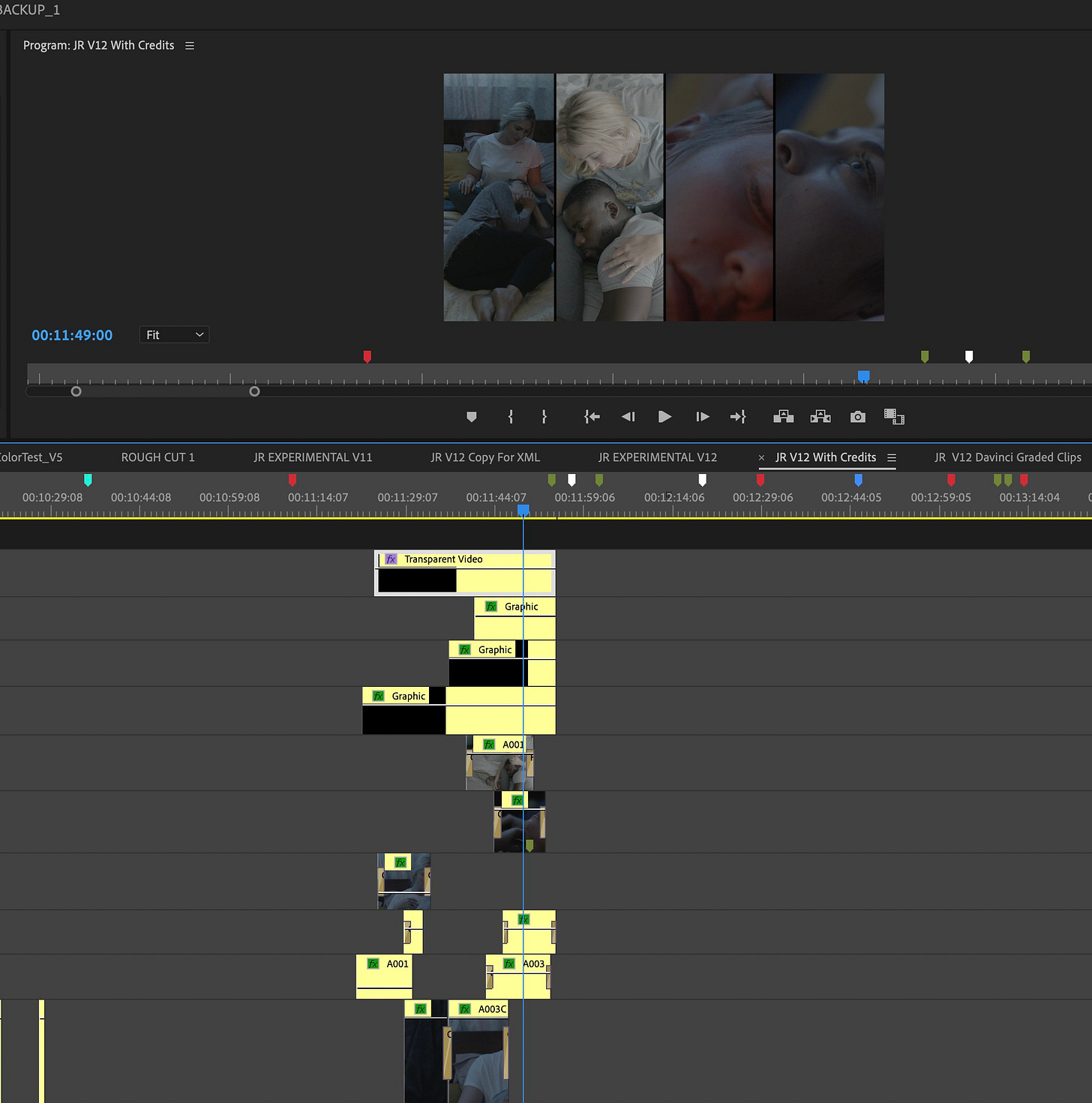

Anderson had recently watched a film, I recall it being “The Green Hornet” remake, or something similar, and had mentioned in one of our phone calls that there was a section of the film that utilized the use of split screens that divide the screen and creatively move around to create a comic book style of framing and editing.

He sent me a YouTube link of the scene and I found it quite fun and impressive creatively. He then suggested we try out bringing in split screens into the cuddling scenes between Lucy and the clients.

It took me a little bit to picture it, but the more I thought about it I quickly realized it was an absolutely brilliant idea. It would be a creative way to not only showcase multiple cuddle positions in the same frame, but could help serve to break up the long middle section of the film by adding some creative flair and creativity and bring some fun and experimental editing techniques into the film. As unique as the subject matter of the film was, it became crystal clear to me that the editing had to be unique as well.

I will also admit that it seemed like a major challenge and presented some incredibly intricate experimentation, but also would make the film stand out visually and showcase that some additional effort and artistry went into the film and this was a major appeal to me. I also loved that it created a challenge to problem solve and I wanted to be able to show viewers that I was willing to go above and beyond to deliver a film that you couldn’t put in a box, (well only this scenes) so to speak. All of my favorite films feel like they were incredibly difficult to have made and I wanted to rise to that occasion with this film and take big risks, otherwise it didn’t feel worth making.

In theory the split screen presented a fantastic array of possibilities without ever having to shoot an additional frame of new footage.

In practice, this became the most difficult section of the entire edit by a long shot. I spent days and days trying out hundreds of variations of the split screen. I tried 8 frames, 6 frames, dissolves within a frame of a frame, animating boxes of the frame to move around, you name it! Not to mention that we had to animate the frame lines being drawn and at what point they would come in was all incredibly tedious, especially since we were far out of the realm of the script at this point and there was no roadmap of how it should look.

The tedium came in thousands of options to choose from and feeling the need to explore as much as possible within that. At some point I realized I had to stop and make conclusive decisions about which shots and how the frame lines would be drawn.

I ended up settling on starting with two frames and then going to a total of four frames max to be able to allow the viewer to still see every frame on screen for at least a few seconds. We included a few dissolves within frames to keep the flow of information and tried to keep it as visual and graphic as possible. We virtually removed most of the dialogue in this section except for Lucy naming the titles of the cuddle positions so that the music and visuals could wash over you in a poetic and elegant way.

It was also difficult to determine which shots would be in the four frames, and to be honest this was a case where many experimenting with various options led to some happy accidents that I just kept since it felt right.

The Split Screen Section On the Timeline Below:

Anderson helped animate the frame lines being drawn and finally we had finished the split screen section and it is still one of the parts of the film I am the most proud of. For reference this is a frame below of the four-quadrant section of this scene. This scene begins at 07:10 (7 minutes, 10 seconds) and ends around 07:45 in the short film for viewing reference.

*A quick note for the more technically inclined: What made this even harder was that we had to bring all of the clips featured in the split screen into DaVinci to first grade as individual clips during the color grade. And then we sent those back to Premiere, already graded, to insert back into the split screen edit timeline container and then exported this out again as it’s own sub-clip to plug back into the final color graded timeline that we exported out from DaVinci. Very complicated indeed.

One Last Breakthrough

As we approached our later edits, our biggest conflict was still a bloated runtime. We were still hovering around 20 minutes and while I knew this would be a longer running short film, I still new 20 minutes was too long. My goal was around 15 minutes.

While playing around in the edit and looking through what scenes carried the longest screen time, it always came down to the two client cuddling scenes.

One day the lightbulb went off in my head to try out combining both of them to be one longer passage of a scene that in some ways resembled a montage.

This idea allowed us to not only cut down on overall runtime, but also to trim out some of the repetitive beats of the protocol and language of how a session is run since we repeated some of those in both scenes and they didn’t need repeating.

After combining the two scenes together into what I called “The Cuddle Montage”, it quickly became clear this was our solution to the problem and it further compelled me to look for more opportunities to cut down on runtime.

We ran through a few cuts of the Cuddle Montage, but ultimately got it down to a shorter and more economic way of displaying the clients and also flowed more naturally into the “Split-Screen” section we had already finished, that I outlined above. It was a win-win on all accounts and ultimately got our final runtime of the film to 16 minutes and 25 seconds, which was just slightly above the 15 minute goal I had set.

KEY TAKEAWAY #3: So much of editing comes down to problem solving and narrative economy.

Try Everything

With each cut, you’re really looking to find the voice of the movie and soul of the narrative and I really do believe the statement that the movie will show you what it wants to be, if you let it.

With each cut, I start to hone in on very very small details and finesse certain cut points between shots to make it feel elegant and make it feel seamless as each shot flows into the next one. I’m scanning for things like breaking the 180 degree rule, preserving continuity of movement or body parts and head placement of actors between shots, etc.

In subsequent edits I will try out different variations of how I could edit the scene, based off the footage I have. I liken this to trying multiple numbers on a lock until I find the right combination of numbers that unlocks the code.

I’ll admit that this approach is exhaustive and grueling, but ultimately rewarding because once you settle on the right configuration, you can confidently stand by it anytime you view the finished film eventually on a big screen or in front of friends, family and other filmmakers. You can move forward with no regrets, knowing that you tried every version and the best version of your film prevailed.

KEY TAKEAWAY #4: Try every possible variation of how to edit your film. This exploration phase reveals so many hidden gems and gets you well acquainted with your movie on an even deeper level to tap into what it needs to be and eventually it will reveal itself to you.

The Score

In tandem with the editing process, we also began the process of starting the score and selecting a composer to do the music for the film.

This was a unique scenario for me in that because of our crowdsource campaign through Seed & Spark that we used to get the budget for the film, a handful of composers emailed me with interest to work on the score for the film. What I decided to do was have them do a score sample “bake-off” to see which composer really could nail the sound I was hearing in my head.

A “bake-off”, in industry vernacular, usually corresponds to a situation where multiple creatives or teams all showcase their work in an effort to land a job, typically for a coveted position.

After asking nearly 8 composers to send me a one minute score sample of a clip from the crowdsource video with the music taken out, I settled on a composer based out of Spain, named Paco Periago.

Paco brought an incredibly positive and collaborative energy and our entire correspondence happened over email. I think this created some unique challenges that might have elongated the timeline, but I’m so pleased with what we ultimately ended up with.

I was extremely meticulous throughout the score process, and after Paco sent me a first full pass of scoring the film, I would email him back detailed notes with time codes included for what to change at certain moments. Giving score notes to composers I feel is one of my weaker suits as a director, and one I’m trying to get better at by learning more music theory and composition knowledge.

Working with great composers, you find that they often know how to translate exactly what you are saying into musical ideas and results.

One of the elements I was very set on was establishing a “Cuddle Buddies” theme that acted as a leitmotif, that would become the signature sound of Lucy and Marina’s relationship. Paco created a gorgeous theme, and one of my favorite moments in the film is the very ending when the motif comes back around in the last scene with Lucy and Marina and the score has a triumphant swell as we cut to black and the title card of the film fades in.

Original Song: “Promises”

One of my favorite songs of all time is the song “Glycerine” by the band Bush. It’s a classic of the early 90’s grunge era that exploded throughout the US at that time. I always wanted Glycerine to be the song that plays over the section of the family montage that shows the happy family before the marriage crumbles.

It was a stark contrast in musical style to the rest of the film that had a more orchestral score, and I wanted it to carry that grunge and hard-edged melancholy that many of those songs convey.

I knew it would be a long shot to get the rights to the song for public use, but I tried any way. Getting the “sync” rights requires permission from the publishing company and the record label. They not only both have to agree, but you also have to negotiate what the fee will be to use it and for how long it will be used in the film. Often times this is an extremely expensive process and one no means you will not be using the song in your film, at least in a public capacity.

The publishing company told me no since they didn’t feel it was worth their time to get into any details or quotes since it was a short film and the budget was small. Such is life.

I didn’t want to fully take no for an answer so I contacted a musician friend of mine named Andrew Mason, and asked him if he would be able and willing to create our own original grunge song that felt very similar to “Glycerine” for the montage, but one that we could tailor more personally to the film’s themes and bring in a nice additional score element with to elegantly tie back into the last scene of the film, when we return to the normal score.

Andrew accepted the challenge and we went back and forth to refine the song over about 5 or 6 iterations until I knew we had landed the tone I was looking for and Andrew had introduced this beautiful score element to finish off the harder rock elements of the song. Andrew even wrote lyrics and sang them over the song and I’m very proud that we made our own song and still retained the 90’s grunge within the film that I always envisioned. The montage begins at 09:39 into the film.

Listen to the track for “Promises” below:

Sound Design

As is customary for me, I enlisted my go to sound designer Sam Costello, who has done the post sound design for every single one of my short films since my college thesis film Narcolepsy. Sam and I went to Elon University together and Sam is without a doubt one of the kindest, hard-working, talented, communicative and collaborative people I have ever had the chance of working with. I am the lucky one to be able to have Sam willing to collaborate on so many projects to date. It is completely true that good sound and sound design will enhance your film and transcend it into another caliber of experience.

In one of the earliest discussions we had about this film, I told Sam I loved the idea of bringing in ASMR and very subtle sounds, especially during the client cuddle scenes to make a viewer feel the relaxing sensation and calm and warmth that they would feel in real life in a session, since ASMR has the amazing ability to create a tingly sensation and physiologically affect you from afar, through a screen and speakers.

Sam did multiple iterations of the sound design and did an excellent job incorporating these subtle sounds into the design, while also mixing and mastering all of the audio levels, including fixing rougher audio from the set, mixing the score and original song and enhancing the transitional shots between scenes with eloquent sound FX that he designed and foleyed1 himself.

Sam really is a jack of all trades within the sound realm, and I’m so pleased with the subtle textures and soft vocal qualities he brought out, especially in the client cuddle scenes. I also love that they are subtle and never distract from the narrative. If you listen closely to those scenes, you can hear what I’m talking about and it’s almost invisible and yet feels inherently soothing.

Color Grading

Now that we had completed every other aspect of post-production, the very last task was to color grade the film.

It’s very easy to underestimate how much budget post-production can cost, and at this stage we had just about run out of budget for the film and so in a normal situation where I would hire a professional colorist, I opted to save money and do it myself.

I had done minimal color grading for a few prior projects and felt comfortable using the grading software, DaVinci Resolve, to do the color grade. I am by no means a professional colorist, but knew enough to do it and ended up learning quite a bit about the process along the way.

The grading process was also quite laborious since I experimented with dozens of color LUTS2 and color options and aesthetic choices. I tried out various looks of really pushing the saturation and vibrance and also trying more bold looks that emphasized one color over the other (think “Green” a la the look of “The Matrix” as an example.)

In the end, I found that not over-doing the saturation, but boosting the contrast, highlights and really showcasing the beautiful Panavision lenses we used to shoot the film created the best look to me for this film. I really stuck to a very “naturalistic” look that didn’t feel too processed or filtered and I think this ultimately let the performances and the story shine so as not to distract or feel too “pretty”. I felt that was more of a “commercial” or music video grade that I didn’t feel fit the tone of the film. I don’t think I really ended up using any LUT, but instead just used the other minimal adjustments to bring out the footage.

One other key in color grading is to always view your color on a few different monitors aside from the one you are using to color grade, especially if it is not an expensive and professionally color calibrated monitor, which a real colorist would certainly have. This way you can see how it looks on various screens to give you a more accurate view and show you if you need to refine any further adjustments. For example, I ended up finding out my iMac grading monitor tended to be more contrast heavy, but lacked the same contrast when I looked at the shots on different monitors. Thus, I boosted the contrast more than I thought I needed to in order to compensate and then it matched properly.

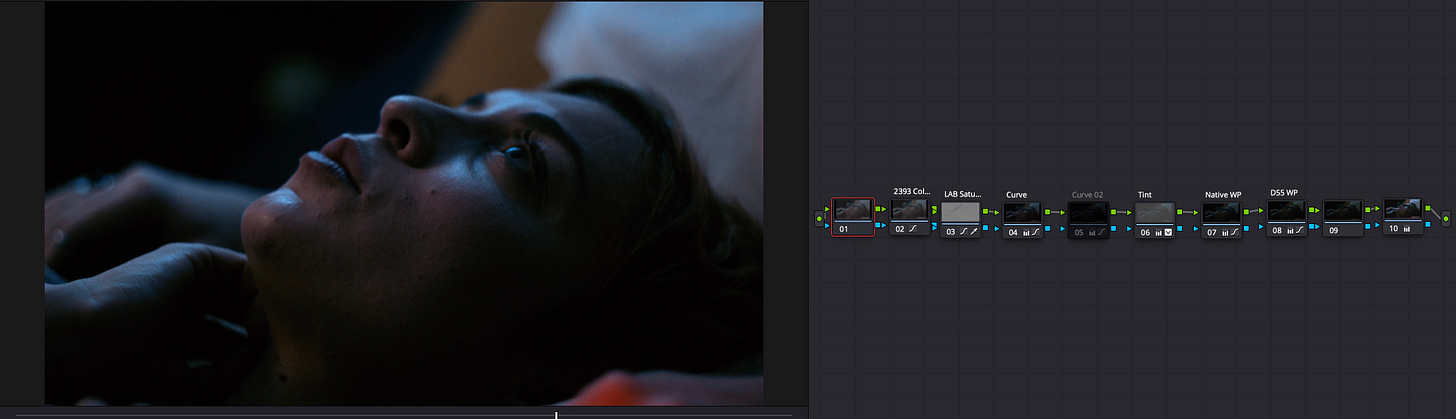

On a more technical note, there was one scene I used what they call a “Power Grade” setup for. In essence, because DaVinci is a node-based software where each node is usually reserved for one specific change such as just highlights or contrast, it is similar to Photoshop, where one layer is used for one thing at a time. A Power Grade is a little bit like a LUT in that you put it onto a shot and it populates a series of nodes chained together to give you the base look. Within that you can alter any node or add to the chain if you see fit.

I found a Kodak 2393 Film Stock Power Grade that mimicked the colorimetry or color science of what this specific film stock in real life looks like. It gives it a very nice subtle grain and texture while keeping the colors balanced and reduces a little bit of the sharp and contrasty digital camera look.

I used this Power Grade for just the Cuddle Montage scene between clients, solely because it created a gorgeous look, especially in the close up shots of Fiona laying on the pillow. See Still Below:

Kodak 2393 Power Grade Node Display Graph

The rest of the film mostly followed a standard grade with the exception of the “Family Montage”, in which I played around with a 4:3 Pillar-Boxed aspect ratio (see below), to mimic an old home video standard definition cam corder video camera. It was fun to see the aspect ratio flip from 4:3 to 2:39:1.

4:3 Pillar Box

2:39:1 Letter Box

The other shot that ended up becoming one of my favorites in the film was a complete accident that occurred through experimentation. I was experimenting with some color looks in Adobe After Effects, since there was one extension cable I had to digitally remove in a shot where it was in the frame and used After Effects to do this.

Upon accidentally layering two shots of the exact same camera angle of Lucy and James kissing on the kitchen table, I noticed that it created this “ghost-like” effect in which it appears that the ghosts of Lucy and James emerge from their bodies in true corporeal fashion. The colors looked fantastic, but it also tied into the theme that we’re watching a ghost of their marriage that has now died and that was a happier time that now lives in the past. That shot is below for reference:

Technical Specs: The film was actually shot with spherical lenses in 2K with the Arri Alexa Classic with a 16:9 standard HD or 1.78:1 aspect ratio, but in post I added widescreen bars to simulate a 2:39:1 letterboxed anamorphic aspect ratio to the top and bottom of the frame. I found that when I added this, it added a cinematic feel and also framed the faces of the actors very nicely in the close ups and put an emphasis on their eyes and expressions.

Delivering the DCP (Digital Cinema Package) file for eventual festival screenings was quite a tricky endeavor to figure out, but more on that in the next installment.

Finishing The Film

Upon completing the color grade, I took a little time away from the film and then came back and rewatched it with some fresh eyes and this proved to be invaluable since it allowed me to make some additional tiny tweaks to the edit that made a big difference to the film, at least in my eyes.

It allowed me to watch with a fresh mind and I highly recommend doing this if you can since you will often catch the smallest but glaring errors that will only be magnified on the big screen later on.

After viewing the film multiple times and making the very last tweaks, it was now time to call it quits and create a series of exports at different resolutions for various platforms.

I’m a firm believer that sweating the details as much as humanly possible allows you to fully lay the film to rest and stop tinkering and I think it’s very important to draw the line in the sand at some point and stop working on it and embrace what you made.

My motto in regards to filmmaking is: “Stress now so you can relax later.” This has been true for every production thus far. Kill yourself now making the film so that you don’t feel the need to in the theatre once it’s too late. (Please don’t take this literally, you know what I mean.)

As far as exports go, I made a 1920x1080 QuickTime Version at ProRes 422, and a full resolution 2K QT at ProRes 4444, along with a compressed 1080 H.264 QT more for reference, and then one more 1080x1920 (flip the 1920x1080) H.264 MP4 version to be able to post onto Instagram or social media platforms so that it would match the vertical aspect ratio that your phone contains.

In total we did 12 revisions of the edit until we locked picture.

Below is a photo of the final editing timeline for the finished film within Premiere:

Cutting The Film Trailer

This was something I only realized later on, but is essential to edit, once the film is complete; make sure to cut a film trailer.

Thankfully I had decided to do this a month after the film was complete, and it was made far easier by the fact that I had a finished and color graded film to be able to choose pieces from.

Sometimes that also makes it harder to try to choose the best moments from your film, but also to choose what to include to try to sell your film and build as much interest as you can from the trailer alone. It’s also important to figure out what type of trailer and the tone you really want to sell from a marketing standpoint. Entire marketing teams labor over these decisions every day, so this is a difficult but crucial decision to make before cutting your trailer.

I spent a few days agonizing over every detail and to be honest I think I got a little bit of the luck of the creative gods in this instance, since I recall just snagging certain clips and dialogue clips that I put over certain moments as if they were voiceover, along with a section of the score Paco made.

I remember just wanting to set up the fact that she is a professional cuddler, but also a Mom and a wife (or ex-wife) and I was very insistent on using the line of dialogue: “So Jeffrey have you ever had a professional cuddling session before?” I felt this line perfectly set up her job but also in a way teased and asked the audience, “Have you ever had a professional cuddling session or heard of a professional cuddler before either?” Such is the marketing thought process, which can vary drastically from the narrative and filmmaking mindset. Why not learn to embrace both as a filmmaker?

I also made sure to include shots of the clients, and Lucy and Marina together to establish the focus of their relationship dynamic and establish a brief view of the narrative stakes for Lucy.

After 1-2 revisions, I was very happy with the trailer and it truly came in handy later since I ended up needing to submit it with the film to multiple film festivals, subsequent screening events, applications, grant programs etc, so this became a crucial asset to have later beyond the post-process that I’ll detail in the final installment.

At this point, post-production was officially complete and we were now ready to submit to film festivals and industry professionals to watch for the first time!

TAKE RISKS!

In conclusion, I can’t stress this enough for filmmakers: TAKE RISKS!

Don’t play it safe, you spent way too much time and effort to do that to yourself or the audience. Show them something they haven’t seen, or at least try to and captivate them. Wow them with how much time and thought you put into the work. It will always pay off, in more ways than one.

I want to end with a quote that perfectly sums up this filmmaking philosophy from my favorite director James Cameron:

“I didn’t get into filmmaking to play it safe. If I wanted to play it safe, I would have done something else…And no important endeavor that required innovation was done without risk. You have to be willing to take those risks. In whatever you’re doing, failure is an option, but fear is not.”

Stay tuned for the next and final installment, Part 5 on “After Post-Production: Marketing, Film Festivals & Beyond”, coming soon!

Next Up: Cuddle Buddies: A Short Film Case Study Part 5 - After Post-Production: Marketing, Film Festivals & Beyond (Coming Soon)

Glossary:

Foley - The process of creating unique sound effects for the sound design of a film. This is a truly unique, innovative and creative position since every film requires unique sound effects. Typically, foley artists will use various objects and sounds to create a specific sound. For example, snapping celery for bones breaking on screen.

LUT - Stands for “Look Up Table”. The best way to describe this is similar to a very strong filter you might put over a photo. It creates a very specific color look within a color space and many people will use a LUT for the base of their film look to further tweak and grade from.